Women on Trial: Cinema, Martyrdom, and the Female Face

- Scarlet Thomas

- Feb 8

- 4 min read

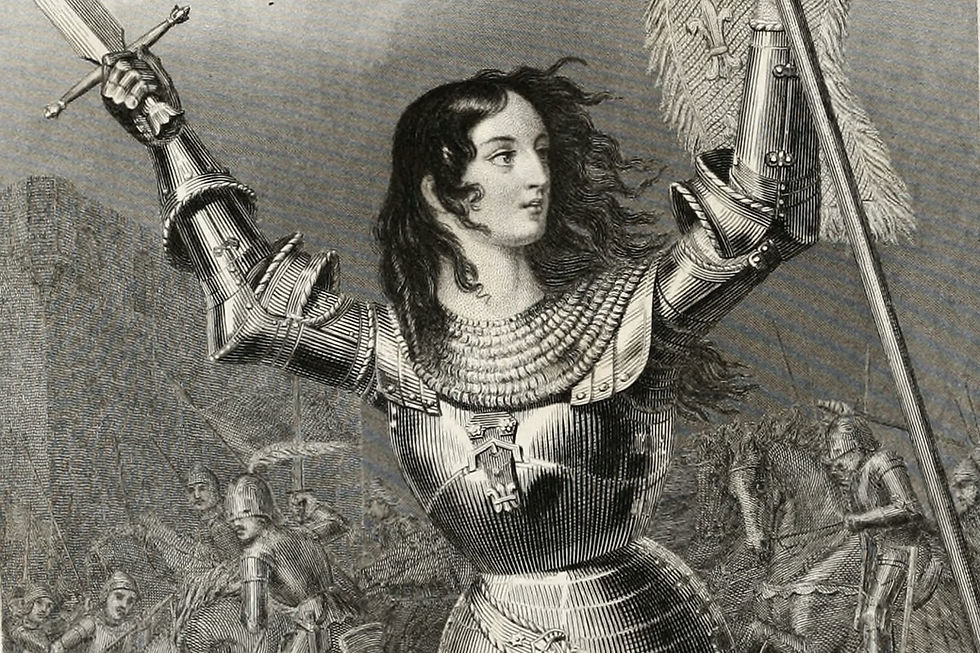

Joan of Arc was born around 1412 in Domrémy, France, to a peasant family during the Hundred Years’ War. As a teenager, she claimed to receive divine visions and went on to lead French troops into battle — an extraordinary act for a young woman in a rigidly patriarchal society. Captured at seventeen, Joan was tried by an English-controlled ecclesiastical court that scrutinised her faith, clothing, and obedience as much as her actions. She was condemned for heresy and executed by burning at the stake in 1431, aged nineteen. Her conviction was later overturned, and she was canonised as a saint.

Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) is not simply a historical retelling of a saint’s trial; it is a confrontation with how women’s bodies, voices, and faces are scrutinised, doubted, and punished when they exceed the roles assigned to them. Joan of Arc is condemned not only for heresy, but for the far greater crime of certainty — of speaking with conviction in a world that does not believe women are entitled to authority, especially spiritual authority.

Joan’s faith is treated as delusion, not because it lacks sincerity, but because it inhabits a female body. Her visions are interrogated endlessly, her language dissected, her clothing policed. The court demands that she explain herself over and over again, as though repetition might reveal a crack, a lie, a hysteria they are already certain exists. This disbelief is gendered. A young woman claiming direct communion with God is intolerable to an institution built on male authority and hierarchy. Her trial becomes less about theology and more about control.

Dreyer’s radical decision to construct the film almost entirely through close-ups transforms Joan’s face into the primary battleground. There are few establishing shots, little spatial relief. Instead, we are pressed uncomfortably close to Joan’s skin, her eyes, her tears. Béla Balázs described the close-up as cinema’s greatest discovery — a way of rendering subjective interiority visible — and here it becomes an ethical demand. We cannot look away. Joan’s face fills the frame so completely that it feels less like we are watching her than being forced into proximity with her suffering.

This proximity produces an unsettling intimacy. Joan’s face is stripped of glamour, framed in harsh light, her skin textured, her head shaved, her expressions unguarded. The judges, by contrast, are often shot from distorted angles, their faces looming, grotesque, fragmented. Power is inscribed visually: Joan’s vulnerability is exposed, while the men’s authority manifests as spatial dominance and visual aggression. Yet despite this imbalance, it is Joan’s face that carries moral weight. Her expressions are not theatrical; they are raw, contradictory, human. Fear and resolve coexist. Pain does not erase conviction.

John Berger’s assertion in Ways of Seeing that “women appear” becomes crucial here. Joan is punished precisely because she refuses to merely appear. She acts. She speaks. She leads armies. She claims divine purpose. The trial is an attempt to force her back into passivity — to make her explain herself into submission. The relentless close-ups resist this erasure. Joan is not reduced to spectacle for male desire; instead, her face becomes a site of ethical confrontation. To look at her is to be implicated.

The film’s treatment of Joan resonates disturbingly with later historical persecutions of women, particularly the Salem witch trials. In both cases, women who deviated from social obedience — who spoke too boldly, believed too fiercely, or existed too independently — were recast as dangerous. Male fear masqueraded as moral authority. Punishment was framed as righteousness. The spectacle of trial became a warning: step out of line, and your body will pay for it.

What makes The Passion of Joan of Arc so devastating is not only Joan’s execution, but the sustained duration of her humiliation. Dreyer forces us to sit with her suffering without narrative escape. This aligns uncannily with Antonin Artaud’s later ideas of cruelty — not cruelty as violence alone, but as an assault on comfort, an insistence that art should unsettle the nervous system. Watching Joan feels like exposure. By the end, the viewer is left raw, opened, unprotected — mirroring Joan herself.

Renée Falconetti’s performance is inseparable from this impact. Her Joan is widely considered one of the greatest performances in cinema history, yet it was also her only major film role. Much has been written about Dreyer’s demanding methods and the emotional toll the role took on her. Falconetti never returned to film and died young after a troubled life. This haunting afterlife complicates the film further. The spectacle of female suffering did not end at the frame’s edge. The cost of embodying martyrdom was real.

As a viewer, I found myself profoundly moved, not in a sentimental way, but in a bodily one. Joan’s face felt almost too close — invasive, confronting, intimate. Her tears did not invite pity so much as responsibility. Emmanuel Levinas writes of the face-to-face encounter as an ethical moment, one that demands recognition of the other’s humanity. Dreyer’s camera enacts this philosophy cinematically. Joan’s face asks something of us. It refuses neutrality.

Nearly a century later, The Passion of Joan of Arc remains devastating because it exposes a pattern that has not disappeared. Women who speak with certainty are still doubted. Women’s pain is still interrogated. Belief is still withheld. Dreyer’s film does not offer comfort or resolution; it offers confrontation. Joan’s martyrdom is not romanticised — it is endured, moment by moment, breath by breath, face by face.

Joan’s power lies in refusal. Refusal to recant, refusal to disappear, refusal to be rendered small. Her face — immense, vulnerable, unyielding — becomes cinema’s quiet accusation. And once seen, it cannot be forgotten.

Comments